Comparando argumentos en contra del Fisicalismo

Juan Camilo Espejo-Serna

Universidad de la Sabana

Plan semanal

Jackson contra el fisicalismo

Fisicalismo

"Toda la información (correcta) es información física"¿Qué significa esta afirmación?

¿Qué implica poner la tesis del fisicalismo en términos de información?

¿Qué es la información? ¿Es esto una categoría ontológica, epistémica o semántica?

La idea central del argumento

"Tell me everything physical there is to tell about what is going on in a living brain, the kind of states, their functional role, their relation to what goes on at other times and in other brains, and so on and so forth, and be I as clever as can be in fitting it all together, you won't have told me about the hurtfulness of pains, the itchiness of itches, pangs of jealousy, or about the characteristic experience of tasting a lemon, smelling a rose, hearing a loud noise or seeing the sky." (p. 127)

El argumento del conocimiento

Fred

Mary

Fred

Fred

Mary

Mary

Fred

Ve más colores que nosotros y aunque sepamos todo lo físicamente relevante sobre su percepción de color, nosotros no sabemos cómo se siente su percepción de color.Mary

Ve menos colores que nosotros y aunque ella sepa todo lo físicamente relevante sobre nuestra percepción de colores,ella no sabe cómo se siente nuestra percepción de

color.

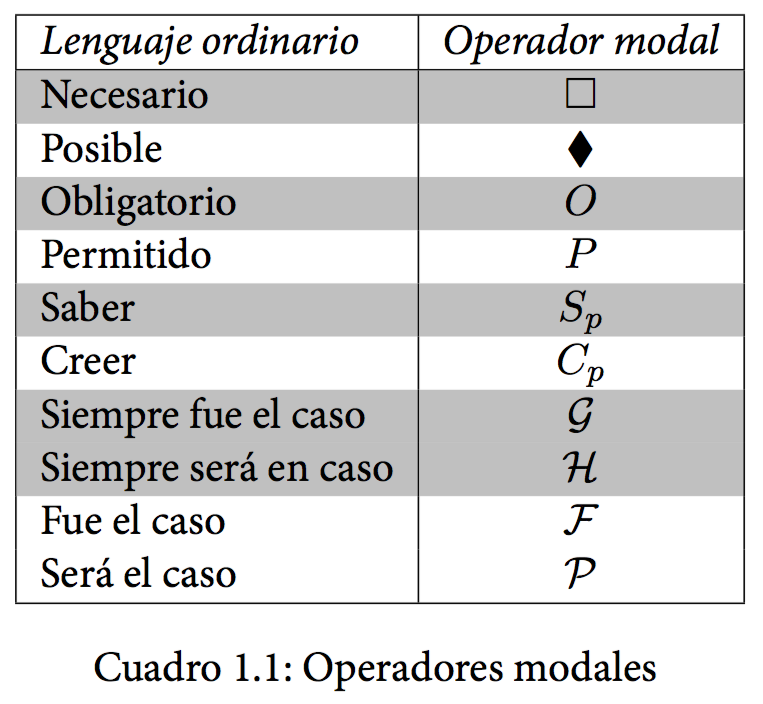

El argumento modal

Porque apela a proposiciones modales

¿Y qué es una proposiciones modal?

- Es necesariamente verdadero que Héspero es Héspero

- Es posiblemente verdadero que todo pueda dejar de existir.

- Es necesariamente verdadero que Juan Manuel no es Sócrates.

- Es posiblemente verdadero que Camila es un extra-terrestre.

- Es necesariamente verdadero que Margarita no come plutonio.

- Es posiblemente verdadero que Nicolás viene a clase.

- Es posiblemente falso que un triángulo tiene cuatro lados.

- Es necesariamente falso que Tatiana no es Tatiana.

- Es posiblemente falso que Pablo es un extraterrestre.

- Es necesariamente falso que Diana no tiene 18 cromosomas.

- Es posiblemente falso que Arturo viene a clase.

Porque apela a proposiciones modales

¿Y qué tipo de proposición modal?

Una proposición sobre lo que es posible

¿Cuál es la proposición modal?

... there is a possible world with organisms exactly like us in every physical respect ... but which differ from us profoundly in that they have no conscious mental life at all.

Dos respuestas

a) El fisicalismo es una verdad contingente sobre este mundo, luego lo que sea posible en otro mundo no afecta lo que es el caso en este mundo.

b) El argumento modal presupone que tenemos una intuición sobre la verdad de las proposición modal. Pero parece que eso dependen de precisamente el tipo de cuestiones que estamos evaluando.

El argumento del punto de vista del murciélago

"In "What is it like to be a bat?" Thomas Nagel argues that no amount of physical information can tell us what it is like to be a bat, and indeed that we, human beings, cannot imagine what it is like to be a bat. His reason is that what this is like can only be understood from a bat's point of view, which is not our point of view and is not something capturable in physical terms which are essentially terms understandable equally from many points of view." (p. 131-132)

"Nagel speaks as if the problem he is raising is one of extrapolating from knowledge of one experience to another, of imagining what an unfamiliar experience would be like on the basis of familiar ones. In terms of Hume's example, from knowledge of some shades of blue we can work out what it would be like to see other shades of blue. Nagel argues that the trouble with bats et al. is that they are too unlike us. It is hard to see an objection to Physicalism here. Physicalism makes no special claims about the imaginative or extrapolative powers of human beings, and it is hard to see why it need do so." (p. 132)

Mini-ensayo

Construya un par de ejemplos como los

de Fred y Mary para una modalidad

diferente de la visual.

Para la próxima

- Jackson, Frank (1986). "What Mary didn't know". The Journal of Philosophy 83: 5. (★)